My dad died on January 13, 2003, 20 years ago today. Though for most of my life he had been my greatest ally and my most kindred spirit - I adored him - we were estranged when he died and that fact remains my deepest sadness, a grief that has remained acute where others have softened.

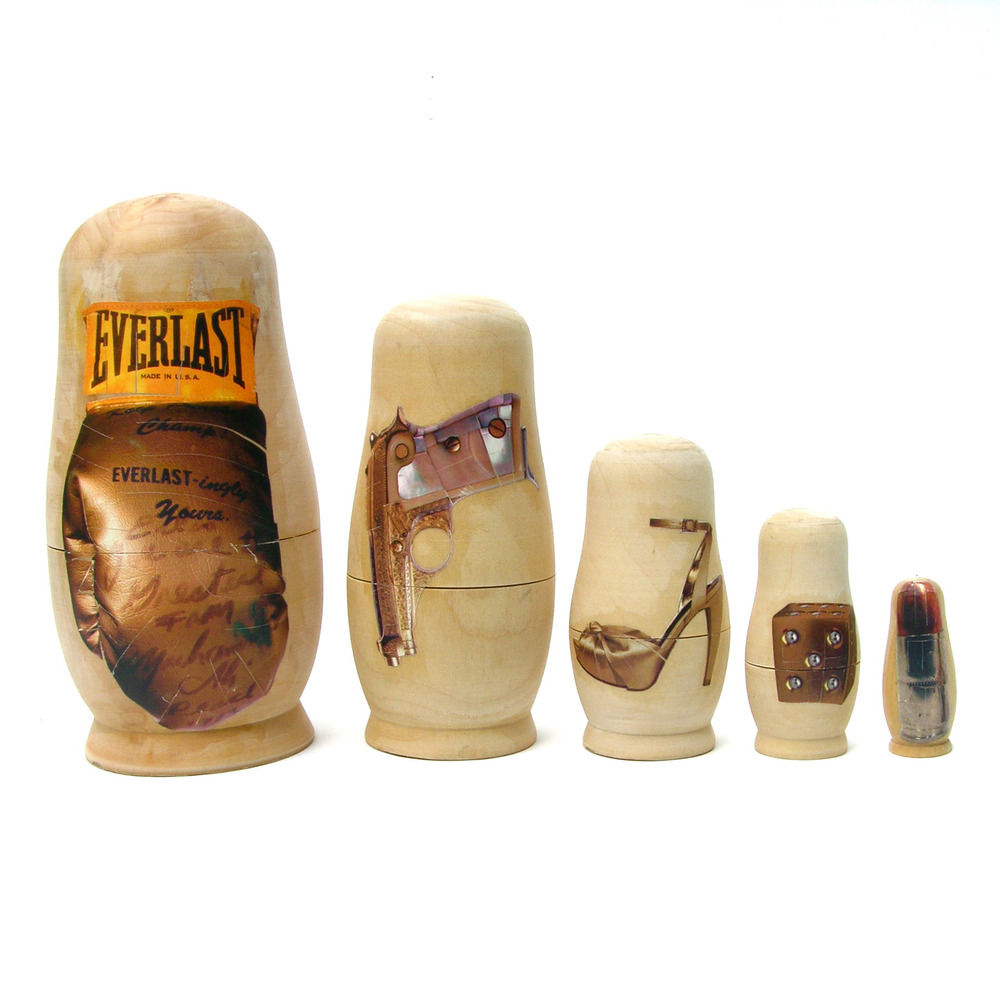

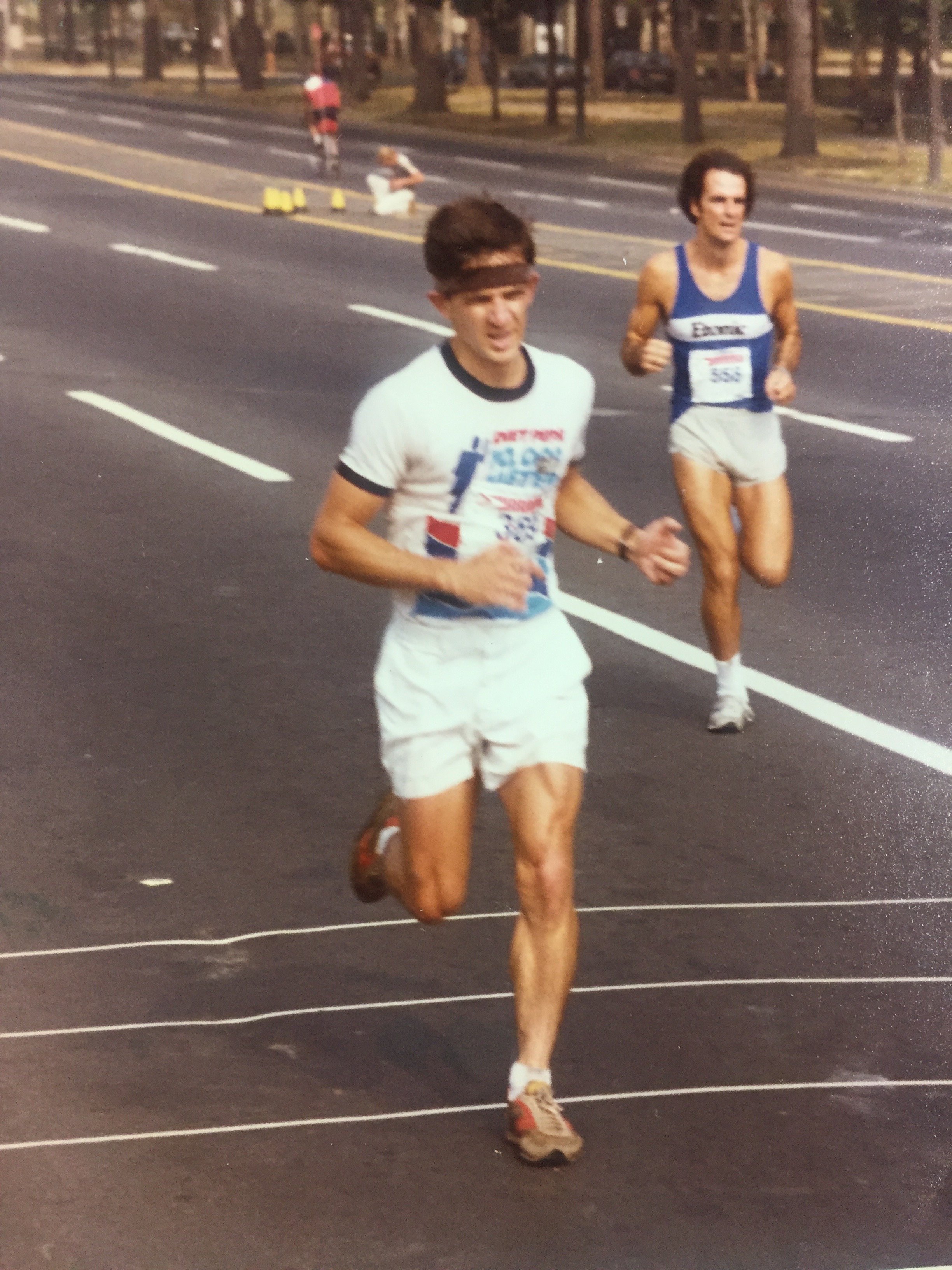

My dad’s most defining qualities were his tenderness, his musicality, a delicate meticulousness, a persistent guilelessness even though he was a broker in the 1980s, his lack of want but for the most simple things, and his ability to run. I don’t know how many races or marathons he ran but I have both the memories and souvenirs (t-shirts, medals, ribbons, engraved silver bowls and platters) to account for their multitudes. He once ran one-hundred miles in less than twenty-four hours around a track. He’d been raised in an orphanage from age three to thirteen where he was abused and his life there took a place inside of him from which he was always trying to distance himself. He was running on a treadmill at a gym when he dropped dead of some paroxysm of his heart. He was fifty-nine years old. He was meant to be the first of his male relations that we knew of to live to sixty.

I never ran with him. I never ran. I danced. But my love of dance and my dad’s love of running manifested themselves with the same devotion. I remember him wearing a Santa hat for his Christmas Day miles and if he were here, he would remember me packing up my presents into a backpack to take them two hours away to the theater where I would spend Christmas, at only 10 years old, dancing. It was on that car ride into the city on that Christmas Day that he told me how much his orphaned life was like the one that I was acting out on stage and he told me that he’d run away once from his orphanage and though he was caught and punished he’d never stopped running.

My dear friend Michael was a retired dancer turned stage manager who reminded me of my dad. Michael ran. We were on tour together. As I was a performer and he was part of the crew, he flew ahead of me from city to city and always seemed to already be out for an exploratory run whenever I arrived at our new hotel in a new city. I regret that Michael and my dad never met, let alone went for a run together. And I regret that the three of us never were able to follow up that run with beers, as a robust appetite for lager and stout is something that we all three shared.

Two years after my father’s death, Michael was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given six months to live. He lived for two more years instead and he ran the Boston Marathon in that time and in between chemo treatments. During his last summer, as he was failing and wanting to fail privately, I struggled to find things to talk about with him on the phone when we’d exhausted the recent plays of the Yankees and he could no longer drink beer. His life had become cocooned in his cancer and its management. So I decided to run the New York City marathon to give us something to talk about. The impulse was efficacious and his job as my coach seemed to give him a strong second and last wind. Michael died on September 30, 2007.

I ran the New York City marathon on November 4, 2007 and subsequently the Paris, Berlin, and Boston Marathons, raising about $10,000 in total for cancer charities. There isn’t a mile that I run that isn’t communion with my two runners, two men I’d desperately love to have more time with and often see so clearly around our dining room table laughing with me and Troy and Henry. Two men my other two men will never meet.

When I was pregnant, everyone told me that exercising would put a kicking fetus to sleep. Instead, when Henry was in my uterus, my activity only seemed to rally him. When I’d try laps on top of my big belly at the Red Hook pool it felt like he was so vigorously swimming along with me that he might tip me over.

When he was a baby in a bouncer on our dining room table I’d multitask mothering and exercise by playing records and dancing the full choreography of Jellicle Cats, I Hope I Get It, Maniac, and 76 Trombones for him. He’d bounce gleefully if I was in the zone but the moment I lost an ounce of authenticity or marked it or tried to phone it in, he would begin to scream.

Henry has engaged on a frequency so high and so constantly that my heart rate seems not to have settled to resting in nine years. He’s fantastic and my favorite person in the world, though I see a future for him as an interrogator for the CIA. He can effortlessly break a person with relentless extroversion.

Henry and I put more than 500 miles on our running stroller before he grew out of it, before I had to stop stuffing him into the seat, his feet dragging on the ground. But whereas I would see other mother-runners with their docile, or more often, sleeping children, Henry talked through every mile. He would point to and comment on everything and if I did not have an immediate and insightful response to his comment or query, he’d repeat his thought, like a scratched record, until I could be a better interlocutor. I think it was Jane Fonda, in her workouts, who told us that if we couldn’t hold a conversation while aerobicizing, we were not in good enough shape.

Before Henry turned one, I learned of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s membership that allowed a year’s worth of entry to the New York Aquarium, Central Park, Queens, Prospect Park, and Bronx Zoos for little more than the price of admission for one day.

Until I learned about the WCS, zoos had made me sad and uncomfortable, as I’d sooner put humans in cages than a tiger. But I learned that the parks under the auspices of the WCS (and many zoos across the country now) are more sanctuaries than the outmoded, unethical notions of a zoo. Many of the animals there are rescues and many are endangered species in captivity in order to breed and sustain their populations before being reintroduced to their native habitats.

It took a lot to pack the heavier, running stroller onto the subway with a small child in order to spend our days at the Prospect Park or Central Park or Queens Zoos, especially as our local R train has the highest elevation subway platform in the world and has no elevator. Then we discovered the Bronx Zoo. The Bronx Zoo has multiple parking lots to which our now Legacy Membership is included.

The Bronx Zoo is over 265 acres, almost all of which are covered in trees and vegetation. The temperature is 10 degrees lower than the rest of the city in the summer. It smells differently. The plants buffer the sounds of the city like snow and there is a quiet that is restorative.

The Bronx Zoo is the only place in which I have ever known Henry to stop talking.

He watched. He listened. He was transfixed there, as, in turn, was I. It became our happy place.

Before our romance with the zoo, Henry had fallen in love with walruses on YouTube. When his peers were snuggling with stuffed bunnies, Henry lived for 2,000-pound, snorting, tusked, pinnipeds. His affections were strongest for a particular orphaned bull named Mitik, rescued in Barrow, Alaska and brought to the New York Aquarium where they were building an exhibit around him when Hurricane Sandy devastated the facility and Mitik had to be rescued and moved again. Mitik had already left New York by the time we went looking for him but his mark was made in our family as our dog, a rescued pitbull, is named Walrus.

The genesis of Henry’s second crush was on our first visit to the Bronx Zoo when he saw a pair of Southern White rhinoceros half-brothers named Harry and Zubari. He saw the two and was smitten. He slept with and carried around two matching rhinoceros stuffies after we’d trimmed their ear hair to reflect the method we’d devised to tell the real rhinos apart: Harry is less Hairy on the ears.

We baked rhino cookies and sold them in order to ‘adopt’ a blind rhino named Maxwell from the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya. I read Dame Daphne Sheldrick’s memoir, “Love, Life, and Elephants” and found a new hero.

In 2017 Henry wanted to dress up as a rhinoceros to attend Boo at the Zoo, the Bronx Zoo’s Halloween party. I made him a papier-mache rhino head and put a tail on his gray pajamas. I was taking photographs with him at the Katherine Weems rhinoceros statues outside of the Zoo Center when we were approached by a rhino keeper who asked to take his picture with Henry in his costume. We would not have been more awestruck if it had been Thomas the Tank Engine or George Clooney. We’d met a man who feeds and scratches Harry and Zubari! It’s his job!

To this day, on our regular visits to the Bronx Zoo, the first thing we do upon entry is visit Harry and Zubari. The last thing we do, after I’ve procured my coffee for the drive home, is say goodbye to Harry and Zibari. On a recent visit, our now friend, Brent, the rhino keeper, surprised us with a visit to their enclosure where we got to watch the keepers feed them and where we got to scratch and whisper sweet nothings to them ourselves.

Our trips to the Bronx Zoo have persisted as some of my happiest days, so much so that I realized I dream of becoming a zookeeper. I can’t do it now as I am still, and still want to be, Henry’s caregiver for longer hours than if I had a job outside of the home but I’d like for it to be my retirement career. In the meantime, I’m building my menagerie on our property for both our happiness and the prerequisites.

The terminus of all this sharing is to tell you that on April 23, 2023 I will run the London Marathon as part of the Save The Rhino International team, raising money for their tremendous and ambitious work. My running and fundraising is a wedding of all these shared intentions; a neat and fulfilling way to remember my dad and my friend and to share their memories with Henry and with Troy and with you and to move forward into a future I’m grateful to plan.

Pour one out for Marty McGehean today (whose drinks of choice were Heineken, Guinness, Bailey’s Irish Cream, and whiskey) and then toast two new Javan rhino calves who have just been spotted in Indonesia and who are the best hope for the population of a species of which there are only eighty left in the world. Among myriad global efforts, Save the Rhino International supports protection units in and around the Javan rhinoceroses’ habitat, where illegal activity threatens their survival. If you feel so moved, please donate to my marathon fundraiser and post a message about something I’ve written here that means something to you. Thank you.